Latest Event Updates

Women at work – is the French model better?

I cannot help making some comments on the great article France’s baby boom secret: get women into work and ditch rigid family norms that has appeared recently in The Guardian. As I have a privilege of being familiar with at least three labour market systems (the “ex-soviet”, German and French), I will make an attempt to take a critical look at all three and try to combine some of their best features into a “perfect solution” for working women.

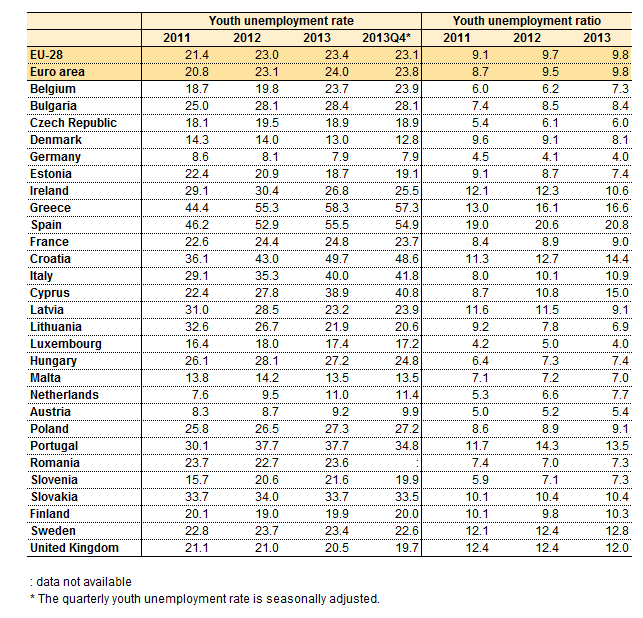

One of the main messages of the article is that “fertility in Europe is higher in countries where women go out to work, lower in those where they generally stay at home”. Now, I do not see the article as a manual for increasing fertility rates in Europe or elsewhere because my strong belief is that population growth is the last thing our planets needs today, taking into consideration all the environmental threats caused by human economic activity such as climate change, overfishing, soil depletion etc. Some researchers even state that the digital revolution actually facilitates job loss because “inefficient” humans are are replaced by machines, computers and software (citations on this subject will come later because it is a big and exciting topic in its own right), while new jobs are not created in a sufficient amount. So the message is that before we try to increase birth rates, countries should figure out what to do with all the unemployed citizens (e.g. 10.4 per cent in France in Q4 2014 according to Insee, 23.7 per cent in Spain in January 2015 according to Trading Economics) and youth unemployment rates are even more alarming in many EU countries (see Figure 1).

So what I like about the article is not its focus on fertility rates, but rather what these birth rates reflect – they show that in countries like France or Sweden, women are actually not afraid of having children because they know that being a mother will not disqualify them as an employee, and working will not qualify them as bad mother. “In France, women who carry on working, even when they have children under three, are not regarded as ‘bad mothers’, thanks to pliant social norms with plenty of latitude. In Germany, on the other hand, they are often accused of being Rabenmutter, by analogy with crows which are thought to abandon their chicks when still young. The old rule of Kinder, Küche, Kirche [children, kitchen and church] still holds.”

I found especially interesting that the map of fertility rates in the EU is remarkably similar to that of childcare facilities. “In former East Germany fertility is higher than in West Germany,” says Lesthaeghe. “The dividing line, which coincides with what was once the Iron Curtain, reflects two different traditions for the care of small children. There were and still are more nurseries in the east than the west. There are similar contrasts between Flemish cantons in Belgium and neighbouring districts in Germany: fertility is higher on the Belgian side, with ample room in nurseries, longer school hours and better organised out-of-school activities, all of which enables women to have a career and a family.”

This information supports my earlier reflections on the conditions for working mothers in Germany. However, I absolutely do not want to say that conditions in France are perfect – far from that. For example, while parents in Germany have the right for a total of 14 months of a financed maternity-paternity leave, in France it is only 3 months! So the majority of French babies are 100% formula-fed from that age. Well, it might be good for the economy (and especially for the formula producing industry), but is it good for the children? Not so sure. For example, the WHO recommends exclusive breastfeeding up to 6 months of age, with continued breastfeeding along with appropriate complementary foods up to two years of age or beyond. While it is clear that formula can never be as good as breastmilk, regular tests (for example by the German Oekotest) suggest that it can be even harmful due to the presence of toxic substances. That is why it was clear for me from the very beginning that my children would not take any formula and I was very happy they were not born in France for this reason.

On the other hand, I am absolutely not a kind of mother who leaves her child at home until the age of three like many Germans and Belarusians do. As soon as my children passed this very sensitive first year when they are very much dependent on the mother for food and care, I was glad to start working and doing research again, while they learned German at their nanny’s. In my opinion this is the perfect approach for both children and parents (the golden middle) – more possibilities for childcare (e.g. breastfeeding) in the first year, and more possibilities to work after that. France has managed to organise the second part but neglects the biological role of a mother when it comes to breastfeeding and caring for a baby. Germany, on the contrary, does well in the first part, but does not offer a sufficient childcare system after the first year. So if we could remember that a woman can be both a mother and a valuable employee, and combine the two systems, that would be perfect! Caution, I do not mean that all French mothers will have to stay at home the first year (I returned to part-time work when my daughter was 4 months old) if the do not want to. But having a choice between working and caring for the child in the first year would be great. Even better would be employers that offer to mothers possibilities to make pauses for breastfeeding at work! Yes, we have been trying to forget that biology matters for a long time and look at what we have done to our planet and to ourselves (depressions, burnouts, suicides, sleep deprivation, employees without any motivation – the numbers are increasing).

The conclusion (as confirmed by the article) is that women (and men) generally need both – family with children AND a meaningful career. In many countries, poor conditions are still forcing them to make a choice between these two options, which is not good for the economy, for the society and for every individual.

Germany should enable a better access of highly qualified mothers to its labour market – Some Statistics

Might this all be just a sign of a beginning paranoia of an exhausted Mum fighting to finish her PhD and to find an open-minded employer? Let’s set aside emotions just for now and turn to hard facts (because apart from being a Mum I am also a researcher), for example, to the brochure Women and Men in the Labour Market: Germany and Europe published by the German Statistical Office (Statistisches Bundesamt) in 2012.

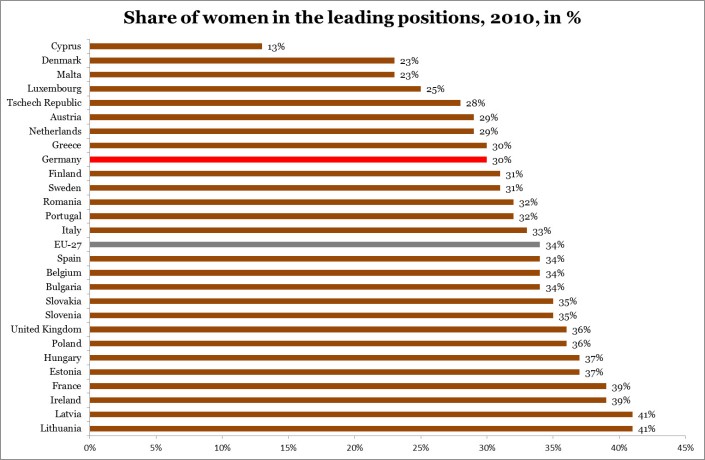

Already in the introduction, the German Statistical Office points out that low participation of women in the labour market leads to a loss of highly qualified employees. Moreover, the statistical office underlines that although there are families that do not follow the tradition pattern, they are still very rare. It is still a rule that women withdraw from the professional life if they have to take care of the family members (like children), while men occupy more important positions and earn a bigger salary. The last idea is supported by Figure 1 – Germany is below the EU-27 average as measured by the share of women in the leading positions in 2010. In the TOP-5, three places are occupied by tree Eastern European countries that must have a well developed childcare system as a legacy from their past in the socialist block.

Source: Women and Men in the Labour Market, German Statistical Office, 2012.

The European Commission in its recent brochure Tackling the gender pay gap in the European Union also stresses that “greater equality between men and women would bring benefits to the economy and to society in general” and that “employers can benefit from using women’s talents and skills more effectively, for example by valuing women’s skills and through introducing policies on work-life balance, training and career development”.

Unfortunately for women working (or looking for a job) in Germany, Germany belongs to the TOP-3 EU countries with the highest gender pay gap (Figure 2) surpassed only by Austria and Estonia! At 22.4 per cent, gender pay gap in Germany is 7 percentage points above the EU-28 average. These differences arise not only from women earning less for the same work, but also from women working shorter hours and in positions with less responsibility as they “bear the burden of unpaid work and childcare”.

These statistics again imply that EU-countries from the former socialist block (e.g. Poland, Latvia, Lithuania) tend to have lower-than-EU-28-average gender pay gap due to women participating more actively in the economic life.

Source: Tackling the gender pay gap in the European Union, European Commission, 2014.

There are also other interesting statistics on the gender equality in the EU, for example “Women and men in leadership positions in the European Union, 2013” by the European Commission. The overall conclusion is that there is still a long way to the real gender balance, Germany included. Legislation such as the quota law approved by the German parliament on 6 March 2015 requiring major companies to allot 30 percent of seats on non-executive boards to women, is a welcome change. As Reuters puts it, “although Germany has been led by a woman, Angela Merkel, since 2005, there is not a single female chief executive among the 30 largest firms on Germany’s blue-chip DAX index”. “A survey published in the Handelsblatt newspaper on Friday said 59 percent of mid-size companies in Germany did not have a single woman in a leadership position, compared to the European Union average of 36 percent”.

So yes, congratulations, well done! But it is yet too early to celebrate at this point because for women to get to the board, they should first be hired by the company and be able to work there more than half-time, which is still hard, because kindergartens are open only until 16:30 and only 60 per cent of children in the primary school in Düsseldorf can stay at school in the afternoon (but in any case not later than 16:30). Taken into consideration that normal office working hours are 9:00 till 17:00 and in many cases, especially in high positions, one is expected to work even later, these conditions cannot be seen as encouraging for women who wish to combine family and career.

Germany should enable a better access of highly qualified mothers to its labour market – Reactions

As the primary goal of my previous posts devoted to conditions for working mothers in Germany was to attract more public awareness to this problem and to share experience with other well educated mothers worldwide, I was very glad to receive the following comment from one of my German friends who lives in Berlin:

As the primary goal of my previous posts devoted to conditions for working mothers in Germany was to attract more public awareness to this problem and to share experience with other well educated mothers worldwide, I was very glad to receive the following comment from one of my German friends who lives in Berlin:

Well done, girl! Thanks a lot!!! Same experiences here: double degree, lots of skills and competences, years and years of working experience etc. but somehow there is just no fitting job available (and I am surrounded by supportive grandparents and extremely good covered child care) … still! I seem to have the wrong age, the wrong sex and well, only one child. What if there might be a second. dear god, nobody could possibly take that risk… very frustrating!

Germany should enable a better access of highly qualified mothers to its labour market – Part I

of the World War II says:

“Women, learn the production, replace

the workers who went to the front!

The stronger is the rearward,

the stronger is the front!”

I am mother with two small children and two university degrees who is currently finishing her PhD in economics. I have been actively applying for qualified jobs for almost a year now – without any success. I am living in Germany – one of the most economically developed countries in the world. And one which you can hardly accuse of (too high) gender inequality.

Born in the Soviet Union, I have been learning as long as I can remember – first at school and then later at the university. Although there was of course no perfect gender equality, women were regarded as important contributors to creating „a better future“ and attaining the economic goals, and girls were given the same scientific education in public schools as boys. It is true that men pursued more often a career of an engineer, while women would prefer to become teachers, but the whole childcare system was and is still adopted to working women. I remember going to a kindergarten and being picked up at 6 p.m. by my Dad as any other Soviet child. After the fall of the Soviet Union, we in Belarus were lucky to have kept the excellent primary and secondary education, as well as higher education that attracted both girls as boys.

Thanks to my well educated parents (my mother holds a university degree in informatics and worked as a programmer for many years while my father obtained his degree in computer engineering) who always encouraged my education, I continued to study eagerly at one of the best technical universities of the country and of course never could even imagine that I was doing it all for nothing. No, I was sure that I was as good as boys (actually I was one of the best in my class at secondary school and university) and that I would still be able to have a family and children while at the same time pursuing a meaningful career. During my third year at the Belarusian State University of Informatics and Radioelectronics I came to Wuppertal, Germany for an exchange semester and was immediately fascinated by the level of democracy that reigned here (contrary to Belarus, there were no ideological slogans in the streets), by the multicultural society and by unlimited opportunities. After finishing my studies in Minsk and graduating in Economics with honours (with a strong technical background), I was awarded a scholarship to continue my Master studies in Germany. So this is how I came back to Wuppertal in 2006 and graduated in Economics (with a focus on ICT and international economics) two years later. Then I decided to continue with a PhD devoted to the analysis of the international mobile communications market while at the same time working as a research assistant at one of the Fraunhofer Institutes, where we developed internationalisation strategies for SMEs from our region based on detailed market analysis. I was mainly responsible for Russian speaking markets with occasional projects in English and French (yes, I speak Russian, German, English and French fluently).